Face to Face: September 2025

ZORICA COLIC

A tongue-shaped vibrator adorned with synthetic black hair; a cracked seashell; a stack of single-use plastic ampoules; a penis-shaped rock; a coil of medical-grade tubing; a plaster dental model clamped down on a blue sponge; a smooth grey stone; a used cast swaddled in opaque waterproof material. This collection, neatly arranged on a shelf in Zorica Čolić’s Upper East studio, reflects the artist’s eclectic material vocabulary. These found and reworked props—the building blocks of Partial Objects, a work in progress—prompt thinking beyond rigid distinctions between the organic and the synthetic, the biological and the technological. From the bisected hot pink dildo featured in The Split (2022) to a plate of surgical screws, these materials charged with uncanny resonance crystallize her ongoing interest in the technological mediation of embodiment and the commodification of pleasure.

The Serbian-born artist, who has lived and worked in this uptown Manhattan space for four years, describes the “seamless” blend of her art into all facets of life. The sheer number of books packed onto her shelves is no surprise, given the layered theoretical references in projects like Cutaneous Vision (2023), a video that brings together Silvia Federici, Anne Boyer, and Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari. Čolić notes her continued interest in psychoanalysis, which has led her to pursue formal psychoanalytic training this fall. Meanwhile, as an artist-in-residence at Harvest Works, she is developing an immersive multi-channel sound installation set to debut early next year. A Voice and Nothing More will explore the externalization of inner thought, while questioning voice as an affectively charged form of translation between realms. Čolić will continue to probe the psychological toll of pervasive surveillance and tightening regimes of censorship today, as notions of the “real” seem more fraught than ever. As our visit came to an end, Čolić shared a last update: the launch of colics, a web store featuring prints and limited-edition t-shirts, all components of larger projects. The offering of wearable goods in particular extends Čolić’s exploration of the visceral dynamics of embodiment throughout all facets of her work.

— Aidan Chisholm

BIRAAJ DODIYA

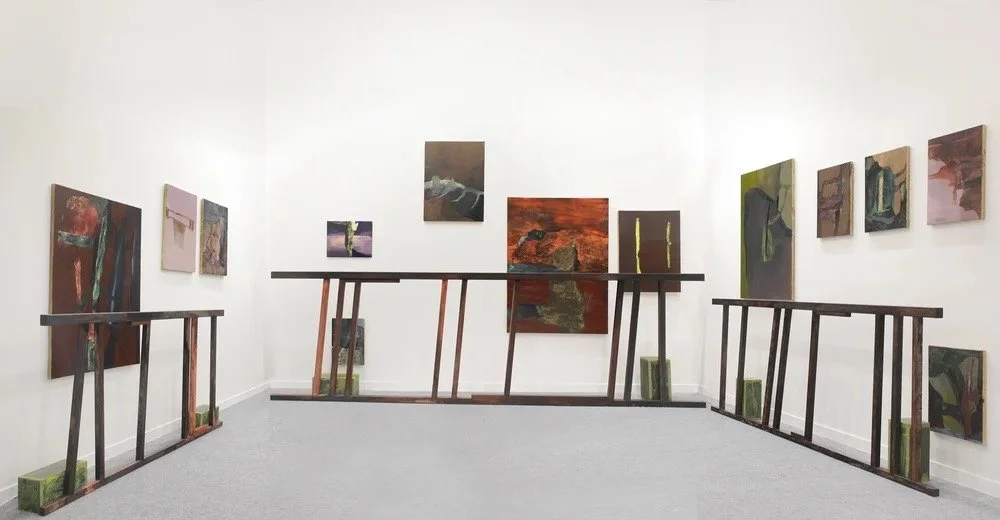

Languages, when shared, when spoken, when alive, fight against not just their own extinction, but also keep a culture alive. Biraaj Dodiya builds a lexicon against nostalgia for bodies in ruin. Her practice constructs meaning against forgetting, creating a visual vocabulary that resists the pull of romanticized loss while directly confronting cultural decay.

Each of Dodiya’s works is not only a solid, meaningful object, but part of a narrative structure that spans her entire practice. If one work can be seen as a word in a language, many strung together can make a shloka. Her colors evoke a moment on the edge of the forgotten—blues, reds, and greens that go in and out of a dark obscurity, trying to maintain agency in the face of an inevitable and all-consuming eventuality. These individual works function as meaningful units in Dodiya's larger vocabulary, each carrying independent significance while contributing to a broader linguistic system of resistance.

Each new installation builds upon the foundation and narrates something entirely new. Multiple works create larger meanings, constructing sentences in this visual language. This develops through her practice as layers of witnessing the ruin are played with and overlaid using photographs within certain artworks, as well as additional artworks in joint installations. The narrative development across installations traces how cumulative meaning emerges, building the grammar of her resistance. The audience’s involvement in being a witness to it creates a dynamic dialogue across her shows. The viewer becomes co-creator in this linguistic system, their witnessing an essential component of the work's completion.

In the face of a slipping grasp on memory, these are persistent acts of clenching one’s fists. The now is the site of a stand against loss, a powerful measure aware of its own temporality, yet revolting against being consumed by nostalgia. A practice that emphasizes the futility of permanence, it is a machine that pumps blood into the liminality between the presentness of memories and the unavoidable fog that follows the march of history. This temporal positioning creates a paradox—acknowledging impermanence while actively fighting against it, using the present moment as the ground for resistance.

Whether one chooses to read them as extremely private ruminations of larger concepts or a divine function towards something foundational, her practice retains the weight of many histories that have shaped the South Asian landscape. This openness of meaning becomes itself a source of resilience, allowing the work to function simultaneously as an intimate reflection and a foundational cultural act.

Biraaj Dodiya is currently in residence at Pioneer Works in Brooklyn, New York.

— Abbas Malakar

AUSTIN MARTIN WHITE

With the opening of his Petzel Gallery show Tracing Delusionships imminent, I found Austin Martin White in a familiar ambivalent mood at his Philadelphia studio in late July: the deliciously ominous inflection point when the labor is just about done and there’s finally enough time to breathe and decide if you actually like the results. Satisfied or not, ambivalence befits his work’s internal tensions.

Most paintings for White’s show were near completion when I stopped by, with a few larger ones leaned against the walls for contemplation. Knocking back Bitburger 0.0’s in the dog days of summer’s heavy heat, he asks my opinion on a pair of them. A smaller piece stands upright on a table drying. Unlike more conventional application of paint to the weave of a canvas, White works from both front and back, pushing pigmented latex through his wide mesh from behind, leaving it spurting out at the viewer. It surges forth in little curlicue tendrils of color that are at once sumptuous and festering, both luscious and rotten. This gives the impression that his subject matter is more emanating from within the paintings than etched onto their surfaces, and a visceral feeling that it is happening in the present tense.

White’s process (which also involves use of a computer-assisted plotter for making marks and producing templates to mask off unpainted areas) alters the relationship of his hand to the work, but never fully conceals it. I feel his touch most urgently in a few recent pieces, verdantly colorful scenes calling back to the history paintings of Bob Thompson. He pulls a Thompson monograph off the shelf for comparison and I see White in Thompson’s shoes revisiting the European canon. Another series he was finalizing suggests a contemporary parallel between us in these United States and 18th century architectural etchings of ruins by Giovanni Battista Piranesi. Neither reference point offers a peaceable vantage with each artist fixated in his own way on desolation: for Piranesi the aforementioned ruins, and for Thompson the Biblical slaughter of children in Bethlehem.

White’s are mostly very large works which can completely absorb one’s field of vision, permitting the viewer to inhabit them as one shelters in the aftermath of a catastrophe. You are in them reaping the whirlwind, which resonates with Piranesi’s personal maxim of “col sporcar si trova.” Translated literally as “you find it by getting dirty,” a more online audience might instead hear the “fuck around and find out” of T-shirts and coffee mugs hawked by increasingly militant far-right influencers. The US is currently finding out. It was, after all, a Roman client state doing the massacring in Thompson’ Bible scene, and then it was the wreckage of Rome that Piranesi surveyed. In White’s work—implied by the “Delusionships” of his title—our mourning is for the demise of a benevolent democracy that wasn’t.

— Joshua Caleb Weibley

ŁUKASZ STOKŁOSA

Visiting Łukasz Stokłosa’s studio was rather unorthodox in that I did not actually visit the studio (he’s in Krakow and I’m in New York). What I have to work with, instead, are fragments: a window framing a sunlit building partly obscured by a tree; a blue figure and a suspended string and its shadow hanging on a wall of peeling paint; mounds of congealed paint, and scattered paintbrushes on the wood floor. But seeing his studio through only these bits and pieces feels somehow apropos.

Stokłosa’s works are small and abundant, inviting a more intimate (and fragmented) viewing approach. Their size, he says, draws viewers closer, shifting the focus from subject to form—not what is being depicted but how it is being depicted. As the distance between us and the canvas shrinks, the vase, or bed, or woman, becomes less and less recognizable, until we no longer see a vase, nor a bed, nor a woman, but paint, brushstrokes, and a canvas. Taking a few steps back and seeing what had, just moments before, become unrecognizable, imbues that thing with a newfound air of mystery.

The emphasis is on bygone opulence—people, interiors, objects—marked by the passage of time. And so it made perfect sense when he mentioned the origins of his interest in this particular subject matter: Luchino Visconti’s film, Conversation Piece (1974), about an aging professor who finds himself both fascinated and repulsed by a set of young and free-loving tenants. The film’s tension lies in a past (the professor’s noble bearing and living quarters) that outlives itself and is distorted by a reality alien to it (the unrestrained debauchery of his youthful tenants). Insofar as it deals with a past disfigured by the present, Stokłosa’s work is similarly constructed.

He works mostly from photos he takes, visiting sites that have outlived their former glory, researching them, photographing them, and painting them. There is a wonderful dialectical quality to the work; much like in Visconti’s film, Stokłosa is interested in a very particular milieu—painting specific people, spaces, and objects, but imbuing them with a kind of otherworldly haziness that places them outside of their respective worlds and into worlds that are both outside of time and an expression of the passing of time itself.

— Rafael Swerdlin

CHRIS HUEN SIN-KAN

Walks in the park where his dogs disappear behind lush foliage and trudge on leaf-strewn paths, his children crafting planetary models for science class, his wife and daughter in their kitchen. These are the scenes that Chris Huen Sin Kan recreates in his monumental paintings, flushed with rich colors and hazy expressions.

Huen recreates moments from his day-to-day life in his paintings, drawing out the “unspoken beauty and quality in the everyday” in his work. Huen’s dream-lit scenes are mercurial and cloudy, reflecting their fleeting nature. Soft brushstrokes punctuate misty landscapes of the Sussex countryside, tracing verdant spaces and canine silhouettes.

“Unforgettable moments actually occupy a very small amount of our time,” says Huen. “I always wanted to paint something bigger, which is the tedious moment.” Impulsivity and spontaneity are intrinsic to Huen’s process; he does not outline or sketch out his work before putting the brush to canvas, and instead dips into his peripheral memory.

Huen refers to his painting process as “tedious” and “unscripted”. In his studio, the massive paintings are propped up on wheels—allowing Huen to turn them towards the wall at his leisure. After a couple months he comes back to them, resifting through his memories and approaching the same scene with a new perspective. The paintings act as a medium to communicate with his past self, engaging in the act of remembering and forgetting.

This uncertainty and ephemerality of Huen’s paintings examines the relationship between subject and perception– are they reflecting a moment, an experience, a person, an animal? The question and answer remain unclear. Huen’s family is not frozen in time, but slowly moving through it, as if underwater. Trivial everyday moments become so humdrum that there is a numbness associated with them in our minds, yet Huen reveals the aesthetic pleasure in their remembrance.

Rather than depicting the best times of his life, like in a beloved family photo album, Huen yearns to represent the small, mundane moments that are so precious to the lived experience. His paintings echo how he perceives his everyday life; they are splashed with the abstract distractions that come with recollection.

Huen’s recent exhibition in London, The Path and the Fog, taking its name from a Milan Kundera passage, evokes the languor, nostalgia, and ambiguity of Huen’s practice.

— Sehrish Alikhan

LEILA SEYEDZADEH

Leila Seyedzadeh has been crafting immersive sculptures of her alpine geography and is ready to flow out of the earth and dip into its cool runoff. Her work is an abstraction of the natural landscape, draping fabric to create dense mountain peaks away from Persian carpets that cover the floors and carefully adorning them with powerful rivers rushing toward the ground. Seyedzadeh is taking materials from the natural landscape and building contrasting, geographic structures that physically impose on a space and force viewers to reflect on the world around them. Her sculptures, made of upcycled fabric and strung from the ceiling, are an escape to the natural environment from the brutality of her metropolitan life.

Growing up in Tehran, the previous topography in her work was inspired by the Alborz mountains, nestled behind the metropolis, which aided audiences’ understanding of her pieces. For exhibitions in the United States, the context of an immediate geographical representation is removed, and the mountains could be associated with anywhere. “I don’t know if the mountains are absent in my life or I’m absent from them,” said Seyedzadeh.

Her new work, Seyedzadeh has pivoted her focus to bodies of water, and while there is an abundance of context, this forthcoming piece is inspired by the East River. She emphasized how necessary time in nature is in order to decompress and create, and has found solace and a sense of belonging watching the water. “It gives me this sense of freedom, pouring into a free water, and also it’s not a real river because it’s connected to the ocean.”

In her newest piece, Threads of Longing, is suspended by visible blue strings, a departure from Seyedzadeh’s previous pieces, which aimed the hide the systems of suspension using clear fishing wire. Beneath the fluidity of the fabric is a ripple of blue, winding above strings and forming a Möbius strip. It has no end or beginning and is full of negative space, something that Seyedzadeh said is an essential element of her art as an immigrant. “You know another language, you know a lot more things, but then there's no ground for you to present it, to express it.”

— Sterling Corum

HANNAH BANG

When I asked Hannah Bang about her preferred medium, the immediate response was “myself.” Bang captures ideas from midair as impulsive gestures that take on meaning through repetition. She enhances the meaning of the word medium.

The impulse for a piece is fleeting, but this ephemeral phenomenon is recorded; the traces left become the piece. In other words, “the idea is the machine that makes the art.”

However, since I had the opportunity to speak with Hannah face to face and ask unprofessional questions about the artist’s intent, I can report more specificity about Bang’s ideas that make her art. In a sort of defiance towards Sol LeWitt’s famous quote, Bang’s ideas don’t escape the physicality of her body. The products of her performances are remnants of a self-grappling process.

“I can communicate with myself most easily,” Bang said. In a piece titled Around Roundy: The Round Things, a gesture strikes her as “the seed of an idea.” Bang invents a collaborative performance out of a simple two-handed gesture, ending in the consumption of a rice cake. An imaginary round thing is held between Bang’s hands, its shape morphing with their movements. Throughout the dialogue of the recording, the shape, its compression, and its expansion accrue meaning. Bang explained to me that this piece was the exploration of her repeated unconscious production of that same gesture that eventually permeated her consciousness and gained significance. It takes its final form as flour, rice, honey, and sugar, only for it to disappear once more in the audience’s mouths. In the performance, the round thing stands for proximity, imperfection, temporality, and a rice cake. The round thing becomes exactly what it is, an amorphous gap between materiality and ideas.

The movement of a gesture from Bang’s unconscious stimulation into conscious behavior is the site of the idea that begins to become the work. To Bang, any of these ideas that are received by the audience is therefore rendered an artwork. However, Bang can be an artist and audience.” Hence, unlike LeWitt, Bang strives less for the Platonic ideal than the subjective impulse. An idea manifests physically and is recognized for its potential as an idea. It recorded for its idea content that is necessarily tied to a physical gesture and slows into form as a piece. Bang catches hold of a positive feedback loop between physical and ideal, where art exists in the interaction between the two, and she is the medium.

— Tobias Olson

You Might Also Like: