What’s Your Pleasure?

Hellraiser is a perfect circle. The film begins with Frank buying a puzzle box to unlock new, deadly pleasures and ends with that box in the same place we found it. It glitters in an exoticized marketplace, waiting. The words of the box’s keeper begin and end the film: “What’s your pleasure?”

Frank’s box casts him into the world of Cenobites. They are self-proclaimed “explorers, in the further regions of experience. Demons to some, angels to others” who seek pleasure through pain. They tear Frank apart, and then his brother Larry moves into Frank’s old haunted house along with his wife (and Frank’s old flame) Julia. Spilled blood resurrects Frank as a gooey corpse who convinces Julia to bring him the bodies of heterosexual suitors to drain. Julia sloppily bashes each rotten man until she must offer Larry to Frank, who takes Larry’s skin to finalize the perverse union. Larry’s painfully normal daughter Kirsty escapes this Freudian hell by, naturally, stabbing her stepmother and fleeing the incestuous advances of her uncle-masked-as-father. The only way to return to straight domestic bliss with a doe-eyed boyfriend? Deliver Frank to the Cenobites, lest they take her instead.

Hellraiser was made for an era of fear around sexuality. AIDS killed, gayness was stigmatized like never before, and naked desire became cloaked in risk. A conservative celebration of normalcy, family, and whiteness prevailed alongside a decrepit Reagan/Thatcher steeliness. It was a moment for patriotism and violent capitalism. Filmmaker Clive Barker met the straight ’80s with a Faustian pickup good enough to separate the libido from flesh-destroying pleasure and the pleasure of destruction.

A hallmark of Hellraiser’s 1987 release was its odd diplomacy. It was cut, written, and designed as an S&M text for broad commercial audiences. It is inoffensively disgusting, possible to be read literally as gay vampires seeking straight blood for weird sex, for virility, and for obtuse pleasures until they can be banished to hell. It can also be read as a championing of monstrosity over the faulty structure of heterosexuality. Even as objects of terror and scorn, the diseased vampire is always more attractive, the fetishists fetishized. The square or uninitiated who meet Barker’s Cenobites cannot help but barter with them. This is because normal, when faced with the fantastical, is always hopelessly overrated. Straights seem to wonder, is the sex worth it? Barker says, “I like monsters to talk,” and when they talk, monsters can be eerily convincing. Viewers were/are sharp enough not to come out of Hellraiser valorizing Larry or Kirsty; they emerge thinking of “Pinhead,” who chooses perversity and pain for himself and offers it to others. That is horror heroism, a deal for a better fuck for all of us.

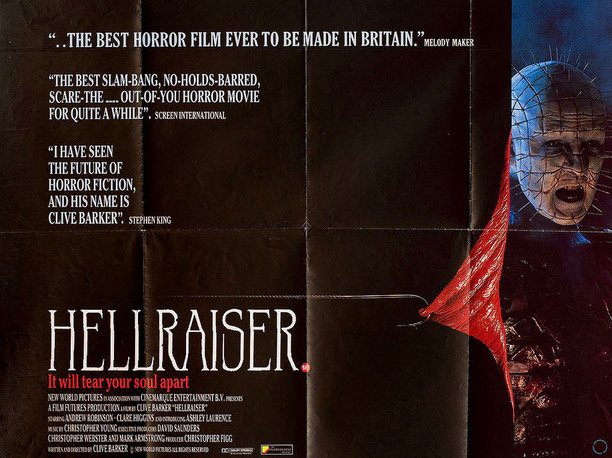

Last week, Hellraiser returned at the New York Film Festival as a restoration by Arrow Films. Barker’s original aspect ratio is there, his original 35mm print is scanned and restored in 4k, stereo sound booms, and there is a simple joy in S&M demons clear on the big screen. Restorations are always novel, sometimes indicative of lost and found material or reappraisal, but not much age is felt here. Barker’s film is no artifact; it reappears for the initiated and glimmers just as dangerously to new viewers.

Barker mentions making Hellraiser as a serious horror film in opposition to the ironic. Now our culture is held hostage by irony. Dominant art infantilizes in the name of broadness, regurgitating a tidy, increasingly state-sponsored algorithmic slop. Sex has no place here; sex divides, shocks, and implicates. Sex is unsafe. In 1987, sex and sexuality were discussed and processed through their depiction. Sex was a part of genres, open discourse. Nowadays, we understand sex and otherness in modern art through lack—we turn to the past, to fringe, to Hellraiser.

Barker recounts, “Here is a woman in the form of Julia, who has a sexual relationship with her brother-in-law in her husband's skin. Here is a girl who is almost sexually molested by a man who is her uncle only lacking a skin. I would have liked a lesbian thing too, but we couldn't fit it in anywhere.” When sex appears in modern film, it is sometimes investigated for its purpose (for the sex-negative, there must always be purpose). For those watching the characters in Hellraiser search for “further regions of experience,” purpose can only be determined by experiment. In the embrace of Hellraiser, sex can feel just as unsafe, as excitingly raw. Is it so strange to desire dangerously?

What a gift and a curse for Hellraiser to live on as a subversive text. What a power to still draw crowds of society’s discarded, to still disgust and turn on. Like the structure of its plot, the afterlife of Hellraiser is a perfect circle. Still illicit, still sexy, and still cutting. And now, we may see the pain and the goo and the knives and the fear ever clearer. That is my pleasure.