Panel Discussion: Art and Climate in Dialogue

Introductions

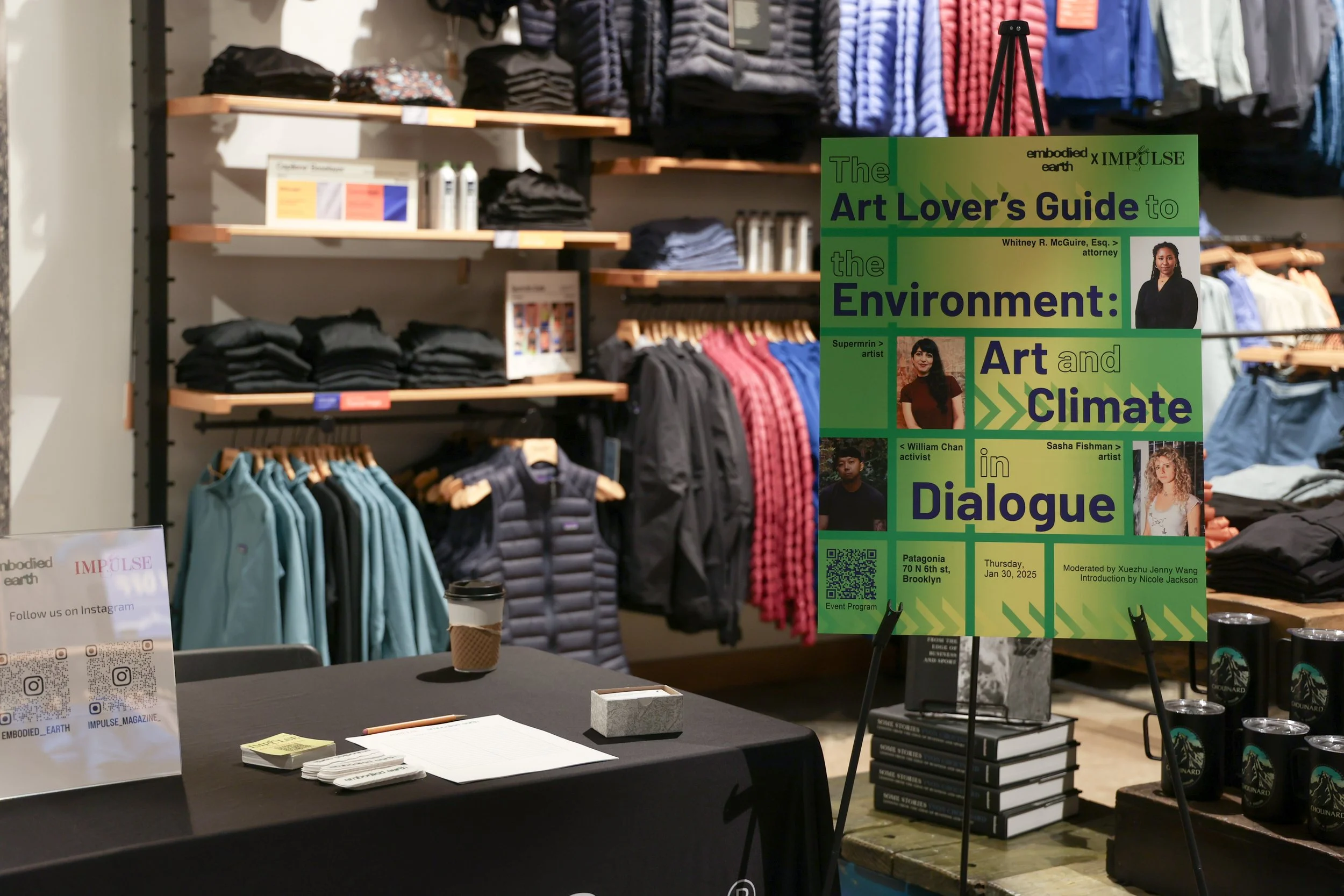

Nicole Jackson: Hello everyone, and welcome, thank you so much for being here tonight. My name is Nicole Jackson, and I am the Founder and Executive Director of Embodied Earth. We are an interdisciplinary arts organization that brings together artists, choreographers, performers, and researchers to investigate the climate crisis through artistic disciplines and practices. We are here tonight in partnership with IMPULSE Magazine, and we would like to thank our host, Patagonia Brooklyn, for letting us use their beautiful space tonight.

This year is off to a grim start. I’m sure we’re all kind of feeling it. For the past fifteen months, we’ve seen humanitarian and ecological devastation in Gaza. We’ve watched fires engulf Los Angeles, displacing tens of thousands of people and ravaging a hub for arts and culture. In the past week alone, the Trump administration has moved swiftly to hurl us further into climate catastrophe through a series of executive orders. The slew of confusing policy decisions actively sacrifice the environment, humanitarian aid, and human health and safety and jeopardize our ability as arts professionals to confidently do our work and support ourselves.

These uncertain and maddening times make me all the more grateful to gather here today with all of you. I’m sure we would not all be here on a Thursday evening if we did not believe in the transformative power of creative expression and radical imagination as it is embedded in our daily lives, our work, and our praxis. Art has always served as the vital language with which we imagine and express our collective survival, and it has been and must be spoken in conversation with grassroots organizing, technological advancements, and progressive policy changes that move us toward an environmentally just future. Our four brilliant panelists are here today to discuss how they center sustainability, local and historical ecologies and economies, and community care in their professional and artistic practices.

I have the honor to introduce the following:

Will Chan, a mutual aid organizer, activist, and artist. His critical statements on the U.S. invasion of Iraq in 2003 are considered to be one of the most important works in response to the Iraq war. This past fall, his solo exhibition, 20 Years After Iraq was displayed at Fields Project here in New York. His works are taught and held at institutions such as the Tim Hetherington Library at the Bronx Documentary Center, Tate Modern, Yale University, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Brooklyn Museum, and Harvard University, among others.

Sasha Fishman is a sculptor and researcher based in New York. Her research interests include marine biomaterials, toxicology and energy harvesting as points for critical analysis and mechanisms for sculpting. She is a recent MFA Sculpture graduate from Columbia University, where she collaborated with labs on salmon, fountains, and carbon capture materials. Sasha is a 2024 Puffins Grant recipient and a current Artist in Residence at Smack Mellon.

Supermrin is an Indian artist working at the intersections of sculpture and ecology. Her bio art project FIELD employs the widespread use of engineered lawn grasses as an operative metaphor for a capitalist, colonial mindset that has led to ecological collapse. FIELD has been featured in Lund Humphries’s recent publication, Towards Another Architecture: New Visions for the 21st Century, a critical rethinking of Le Corbusier’s legacy in the global south in the face of climate change.

And Whitney McGuire, a trailblazing sustainability consultant with a unique 360-degree approach to crafting holistic sustainability strategies for organizations, particularly in the arts and culture sectors. Leveraging her extensive background as a lawyer, founder, professor, and former Associate Director of Sustainability at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, Whitney seamlessly integrates systems thinking, design principles, and legal expertise to drive impactful, long-term sustainability solutions.

Moderating today is Jenny Wang, a writer and art journalist with a background in postwar and contemporary art, design, and architecture. She is the Editor-in-Chief of IMPULSE Magazine, and her work focuses on the intersection of women’s rights and migration.

We hope that you leave today’s discussion feeling encouraged to think ecologically and find the connections between your work and the environment, even if they do not seem immediately obvious. Everything is environmental! Please be sure to stay for the Q & A portion that will immediately follow the panel discussion.

Xuezhu Jenny Wang (XJW): Thank you, Nicole, for the kind introduction. It’s an honor to be moderating the talk today with our four amazing panelists who work in and across different sectors of art, education, and activism.

Tonight we are connected by a shared sense of urgency, and also the conviction that having dialogues and discourses matter. We don’t take our voice and freedom of speech for granted, so we would like to thank Patagonia Brooklyn for the generosity of providing us with a space where our voices can be heard.

On January 20th, Donald Trump signed an executive order titled “Putting America First in International Environmental Agreements,” which directs the United States to again withdraw from the Paris Agreement aimed at global cooperation on climate change. He also declared a national energy emergency as part of a larger plan to push for more oil and gas drilling.

But that’s not all. The administration’s recent orders instruct agencies to roll back restrictions on offshore drilling, reconsider protections for Alaska's Arctic National Wildlife Refuge, and pause new leases and permits for both onshore and offshore wind farms. The US Treasury Department also recently pulled out of the Network of Central Banks and Supervisors for Greening the Financial System, leaving the future of sustainability uncertain and rife with anxiety.

Meanwhile, as a result of the recent LA fires, at least 29 people have died, and over 16,000 homes were burned. The art community has experienced grave losses, with almost 200 artists in the Altadena neighborhood whose homes or studios burned down. Important archives and irreplaceable collections have been destroyed, which leads me to my first general question to all of our panelists: What are we feeling tonight?

Sasha Fishman (SF): I'm excited to be here. There's been a lot going on, and I think discussions like this are so important. These issues will continue unfolding, so it's crucial that we engage with them.

Supermrin (S): It's great to see all of you, and thank you for inviting me. Less than a month ago, I was back in my hometown, New Delhi, for the first time in over five years. My parents are in the process of moving out of the city where they were born. Delhi is one of the most polluted cities in the world right now, and the conversations we’re having today have both highly specific and deeply global implications. I always try to keep that perspective in mind, especially when the immediate realities feel overwhelming.

Whitney McGuire (WM): Hi, everyone. Tonight, I’m feeling anxious. I just saw that a bill was signed into law today that essentially allows for slavery to be blatantly legal—which it always has been, so I guess this is where we are right now.

At the same time, I feel optimistic because I know that community is everything. Existing in a Black body in 2025 is no small feat. I give thanks to my ancestors every day—so first, let’s take a moment to honor them. I also feel grounded spiritually. Much of what I’ve navigated in life has prepared me and others for this moment. Even if I may not be physically prepared—I don’t have a go-bag yet—I feel spiritually ready for the next phase.

Will Chan (WC): I echo everything that has been said before me. But one thing I want to emphasize is that I won’t participate in a discussion that feels like a YouTube lecture in real life. We are all tired of just talking. So when you organize an event, invite us. I’d love to attend. This is what community building looks like. We may not agree 100%—maybe it’s 60%, 70%, or 90%—but I’m a firm believer in democracy, even when it feels broken. If our country fails us, it’s because we’re failing each other—not necessarily the people in this room, but society as a whole.

Still, I remain optimistic. We are here, able to speak out, because of those who fought for this right before us. But I want to stress that there’s no hierarchy here—it’s just a matter of timing. Everyone here brings value to the conversation. Next time, I want to be in the audience, supporting the things you want to create. So let’s sustain this community, not just as passive listeners but as active participants.

Panel Discussion

XJW: Whitney and Will, both of you have worked extensively in fields outside the fine arts. How does the discourse on sustainability in the art world compare to that in other industries, such as fashion, education, and public policy?

WM: Art is dreadfully behind on this discourse. I first got involved in sustainability through the fashion sector. I started as a fashion lawyer, focusing on intellectual property law with a focus on slowing down fast fashion. What I mean by that is, I connected the theft of intellectual property to its direct impact on designers, especially designers of color, many of whom were working in communities facing rapid gentrification. These creators were navigating multiple layers of struggle just to produce their work. I believed that by focusing on intellectual property protections, I could help disrupt this vicious cycle of exploitation that I saw emerging in the early 2000s, which now looks like fast fashion.

I also advocated for garment workers' rights, which exposed me to different spaces of the fashion industry. From a policy perspective, there’s been significant movement on both social and environmental fronts. The EU, for example, has taken the lead in setting regulations and policies aimed at capping the continuous waste stream generated by the fashion industry.

The art sector, like fashion, is full of creatives and also depends on intellectual property protections. But in terms of sustainability, it still has a long way to go. That said, I’m optimistic. Unlike fashion, which is beholden to a specific type of supply chain, the art industry has more flexibility. I also see more creativity in how artists approach sustainability—not just in their materials and practices but in how they engage communities in solution-making. That level of collaboration isn’t as prevalent in fashion. While education around sustainability in the arts is still lacking, I believe we’ll catch up.

WC: My background is in finance. From there, I joined the military, served in Iraq as part of the US Army, and then used the GI Bill to pursue an MFA. I was a fashion photographer with FIT. Since then, I’ve worn many different hats.

The biggest contribution I try to make is calling out hypocrisy. There are a lot of people—whether in fashion, art, or other industries—who say one thing but don’t follow through. And I think that’s one of the biggest problems when it comes to climate change. We all know it’s important, but then we don’t really do anything about it.

That’s why I believe the first step is self-reflection. Before we ask others to make sacrifices, we need to look in the mirror and ask ourselves: What are we personally willing to give up? A lot of my work is about encouraging that honesty—first with ourselves and then with each other. That’s the foundation for real change.

XJW: Mrin and Sasha, both of you have explored bioplastics and biodegradable materials in your work. In recent years, much of the art world has transformed into what is now called the “art industry,” a space increasingly defined by capitalism, waste, consumption, and disposability. As artists whose practices center on natural and biodegradable materials, do you feel that the current industry structure is in conflict with your work and the longevity of the environment?

SF: Yes, absolutely. The way I work has often faced pushback, especially during my time in grad school at Columbia. I had a great experience overall, but I was pushed away from making things that were ephemeral or would degrade and fall apart. There’s a lot of pressure in the art world to produce objects that appreciate in value over time—with materials like metal or plastic. But ironically, many plastics do degrade over time, as we’ve seen with Eva Hesse’s work.

I initially discovered bioplastics and biomaterials through design and fashion because there were all these people experimenting and sharing recipes. It felt like a generative and collaborative space. At one point, I even considered going into material science. Ultimately, I realized that art allowed me the most flexibility—to work across disciplines, engage in dialogue with other fields, and explore materials on my own terms, which is why I continue to make art.

That said, there’s still a tension between process, product, and output. The art industry often expects work to fit neatly within a specific framework, but art itself doesn’t have to conform to that. That’s part of why I continue making art. Some of my materials will outlast me, while others will naturally decompose and need to be replaced. I see my pieces as living beings—things I care for over time. Balancing this approach with the demands of the market is challenging, which is why grants and project-based funding are so important for sustainability-focused work.

S: I can relate to a lot of what you’re saying. I was just telling a new friend that in 2023, I had work in this group show in Chelsea. Fifteen minutes before the opening, they removed my piece from the space because it smelled like grass. I was devastated. There were curators there who had never seen my work before, and this was my chance to introduce them to it. I had flown in specifically for the opening, and there were maybe 20 people there, but they wouldn’t even allow the box containing my work to be opened for a peek. It was incredibly frustrating.

That experience made me realize just how rigid the New York art scene can be—it’s a very specific kind of art world and market. But it’s not everything. There are other spaces I feel more aligned with. A week after that incident, I was on a panel similar to this one, discussing how art engages the senses. It was this beautifully theoretical conversation about experiencing art beyond the visual. And I remember thinking: This is such bullshit. The art world doesn’t actually want to engage the senses—it’s an investment portfolio for collectors.

Ironically, about a week after that panel, a curator approached me and said, “I’ve heard so much about the smell of your work—I need to see it in person.” That’s how I started getting opportunities that were more aligned with my practice.

So, to answer your question: yes, the industry’s focus on material permanence and longevity is in direct conflict with artists working with biodegradable materials. But I think the root of the issue is even deeper—it’s about our fear of mortality. We project that fear outward, onto architecture, onto objects, onto art itself. My background is in architecture, where we were trained to value permanence, to build for eternity. Breaking out of that mindset was incredibly difficult for me.

But beyond the issue of materials, I think we also need to rethink how we frame art itself. Western art history has ingrained a rigid separation between figure, background, and foreground. That division shapes how we construct aesthetics, how we consume images, and ultimately, how we treat the environment. If landscape is always forced to conform to the structure of a portrait, what does that mean for the way we engage with the natural world?

XJW: Thank you so much, and I’m so sorry that happened. Speaking of institutions, I want to turn to Whitney. As the former Director of Sustainability at the Guggenheim, what changes did you implement during your time there? What obstacles did you face, and what challenges do you think similar institutions might encounter in their efforts to move toward a more sustainable future?

WM: Well, let’s start with some context. The Guggenheim was the first major art museum in the U.S. to create a full-time sustainability role—a big deal. I was the first person to hold that position, so unlike other departments with established frameworks and training, I was essentially building the plane while flying it. My first instinct was to coalition-build, so I connected with my counterparts at MOCA LA and the Getty, who were hired shortly after me. We formed a support group because, in many ways, our roles were uncharted territory.

These institutions initially approached sustainability from a corporate perspective—tracking carbon emissions, setting science-based targets, and responding to regulatory pressures. But when it came to actual implementation, there was little guidance. It quickly became clear to me (and others working in this space) that corporate sustainability models don’t translate well to the art sector. So, I had to set that aside and develop a strategy that actually worked within the realities of a museum.

That process started with relationship-building. I identified gaps and pain points within the museum’s operations and sought out internal stakeholders who could champion these initiatives. One of the biggest challenges I faced was the institutional hierarchy, but I also saw it as an opportunity. Hierarchies aren’t inherently bad—they can provide structure when built with empathy.

One of my first major initiatives was working with the museum’s legal team. I realized that our artist agreements didn’t reflect the museum’s sustainability goals. So, I proposed that we invite artists to be active participants in shaping how we approach sustainability. Initially, many people in the institution told me it would never work. But when I brought the idea to the lawyers, they immediately supported it. That was a key moment—I knew how to speak their language, and once we had legal backing, things started to move forward.

I also recognized that curators were at the core of institutional decision-making. Every choice they made impacted the entire museum, so if they weren’t equipped with the right knowledge, things wouldn’t change. I developed curatorial training sessions on carbon emissions—why we track them, how we do it, and why sustainability needs to be a priority. These trainings expanded beyond curators to include registrars and other key staff members, and they were met with strong engagement.

Another major initiative was a materials workshop for exhibition makers, in collaboration with Key Futures (an excellent resource). I also developed a strategic framework for sustainability at the museum, structured around three pillars: Building & Facilities, Exhibitions, and Staff Culture & Community Impact.

Unfortunately, much of my focus had to be on the building and facilities side because the museum lost its facilities director shortly after I was hired. I had to quickly learn about HVAC systems, building management, and local sustainability regulations. I also helped the Guggenheim align with Local Law 97, which requires buildings over 25,000 square feet to report and reduce emissions—50% by 2030 and net-zero by 2050, in line with the Paris Agreement.

On the exhibitions side, we began tracking carbon footprints and engaging artists in that process. We had a lot of success with Cecilia Vicuña’s exhibition at the Guggenheim, where we focused on sustainable materials and reducing waste. We also cleared out storage spaces to create a reuse policy for exhibition materials, ensuring that whatever could be reused was repurposed, and only truly necessary items were stored long-term.

The staff culture and community impact piece was one of the most rewarding aspects of my time there. Our Green Team became a driving force behind sustainability initiatives, inspiring other colleagues to get involved. What I loved most was seeing people take ownership of sustainability in ways that felt meaningful to them. For example, employees I had never met before would come up to me and say, “We have all these extra books—let’s organize a giveaway.” And they actually made it happen—multiple times!

Ultimately, what I’m most proud of is that sustainability became something people across the institution embraced. It wasn’t just my job or the Green Team’s job—it became part of the museum’s culture. That kind of shift is what leads to lasting change.

XJW: That's really impressive. I love that you mentioned holding workshops as a way to bring people to a common ground and speak each other's language to reach a mutual understanding. I also want to direct my question to Sasha, who has been leading a lot of workshops. I attended your algae workshop with Embodied Earth, and it was amazing.

Since you mentioned working with fisheries and collaborating with people who may have very different ideologies and personal politics, how do we get people involved in these larger conversations instead of pushing them away? How do we find common ground for sustainability discussions?

WM: Thank you! Yeah, I love workshops—they're my favorite. But I think the best way to engage people is by building relationships. You can’t just start by telling someone what they’re doing wrong or that their values don’t align with yours.

Some of the people I’ve met in the fisheries have said things that are really surprising to me. But instead of immediately arguing, my long-term goal is to get to know them on a personal level so there's a foundation of trust. That way, they’re more open to sharing details about their daily lives, their relationship to the fish, and their overall connection to the environment.

It can be tricky to navigate these conversations, and I don’t always know the best approach. But honestly, I find it exciting—these are perspectives I’d never hear in my usual circles. Sometimes their views are completely different from mine, and I may never fully understand their reasoning. But at the same time, they have a deep knowledge of seasonal cycles, salmon runs, and animal husbandry—things I could never know firsthand.

I think it’s important to listen, even to those with opposing views. As environmental devastation increases, it’s easy to fall into an "us vs. them" mindset. But we have to resist that urge and remain open to discussion. Spending time with people who think differently from you can be valuable. Even if you don’t agree with them, they might teach you something unexpected. That openness has been a huge part of my research into materials as well.

XJW: Thank you. I also want to bring in Mrin, whose research focuses on agricultural history, its ties to colonialism, and the role of cotton manufacturing in India during British rule as a method of resistance. Given your extensive field research, could you tell us more about how people and power structures have historically interacted with the land? What have you learned from your work?

S: This is my favorite question because I’m basically a nerd. Sometimes I get frustrated when people don’t just give me the information I’m looking for, so I’m assuming if you're here, you enjoy reading and learning about this topic. I’ve put together a list of resources that have really shaped my research, so I’ll go through them quickly.

When I first started, I was looking at grass and its relationship to urban spaces—how architects and urban planners treat nature as this isolated "green box" rather than something more integrated. A key book that helped me was Seeing Like a State by James Scott, which introduced me to German forestry management systems and how they influenced land use in the U.S., Europe, and beyond.

Another influential book was The Invention of Nature by Andrea Wulf, which explores how Western ecological concepts have barely changed since the 18th century. A major turning point in my research came when I read Ecofeminism by Maria Mies and Vandana Shiva. It discusses the connections between small farms, women’s labor—especially domestic and invisible labor—and cottage industries. The book argues that capitalism relies on this unpaid labor to function. If we were to properly compensate domestic work or seasonal agricultural labor, capitalism as we know it would collapse.

This issue ties into the long-standing farmer suicides in India, which have been ongoing since the 1970s. The so-called Green Revolution, which was supposed to improve agriculture, ended up being a disaster. It depleted the soil, drained water resources, and led to economic ruin for many farmers.

One striking fact I discovered is that in the U.S., we now have more lawn grass than all agricultural crops combined—more than corn, wheat, and everything else put together. Yet, we rarely think of lawns as part of our agricultural system, even though they function as a massive monoculture. That’s something I’m challenging in my work.

During India's decolonial struggle, British colonial policies actively suppressed local craft and labor. Raw materials were extracted from India, sent to England for manufacturing, and then sold back to India at inflated prices. It was illegal to make fabric in India for over a hundred years. It was even illegal to produce salt from the sea because the British controlled the salt trade. These were key moments of civil disobedience, like Gandhi’s Salt March, where reclaiming the ability to make one’s own materials became an act of resistance.

I argue that there’s a direct link between small-scale subsistence labor and activism. The way materials circulate—both in historical and modern contexts—shapes power structures. The ability to make things with our own hands, to be self-sufficient, has been intentionally dismantled to make us more dependent on corporate systems.

Right now, we’re in the middle of a material revolution. Across the U.S. and beyond, people are experimenting with alternative materials, sharing knowledge, and working outside corporate-controlled supply chains. We’re trying to create the next generation of materials that could disrupt industries like cement production.

I have more resources if you’re interested—just come talk to me afterward.

XJW: I love that you mentioned the connection between anti-colonial resistance and climate resistance. I’d like to direct this question to Will, who has spent a lot of time participating in mutual aid, including working at shelters. Will, can you tell us more about how you got into activism and how your background in art equips you for this work? What skills from your art practice do you bring to activism?

WC: This could be a four-hour conversation because I’m old, but I’ll try to keep it short. First, just a quick note—this is kind of like a town hall. I assume that what we’ve discussed here can be sent via email, and you can compile it together. If anyone feels like something is missing, I’d love to hear from you. My email is in the program, so feel free to reach out.

Now, back to the question—how did I get here? It’s a long story, but I’ll be quick. I was born in Hong Kong and immigrated to the U.S. as a child. My parents were hardworking but didn’t really understand assimilation or how I was supposed to fit in. Growing up, I struggled with a sense of belonging. I was the only Asian kid in a predominantly white school, which made me question what it meant to be American.

I ended up going to college in Buffalo for finance because my parents wanted me to study business—otherwise, they wouldn’t pay for it. I wasn’t great at it. I worked as a stockbroker in the early 2000s, but it wasn’t for me. Around that time, in 1999, I joined the Army Reserves, before 9/11. In 2001, I was working at the World Trade Center when the attacks happened. That led to my deployment to Kuwait and later to the invasion of Iraq.

For years, I embraced my identity as a combat veteran. It felt like proof of my American-ness. But over time, as the situation in Iraq deteriorated, I started questioning everything. I ended up using the GI Bill to pursue an MFA, which is where I encountered the works of bell hooks, Angela Davis, James Baldwin, and Langston Hughes. That changed everything. Art school forced me to be honest with myself, and I had a moment of clarity—who did I really want to be? That led me to shift from making objects to performance-based work, which in turn brought me deeper into activism.

During the 2020 election, I attended Democratic rallies and started speaking during the Q&A sessions. I pushed back against the idea that Republicans had a monopoly on patriotism. Some of the most patriotic people I know are teachers, doctors, writers, and thinkers. The strongest people I know are mothers—I’m a parent, and I’ve seen firsthand the strength of my son’s mom.

Then the pandemic hit, and I couldn’t do in-person performances. Around that time, I came across the work of Guadalupe Maravilla, an artist and former undocumented immigrant who was organizing mutual aid efforts. I reached out to help and ended up working at a church supporting undocumented communities. These were the same people delivering our food at the height of the pandemic, yet they weren’t getting access to COVID tests, healthcare, or relief payments. That felt deeply unjust. Over four years, that work evolved to focus on asylum seekers, especially in Sunset Park, Brooklyn, where I live.

When people ask me what my art background brings to activism, I tell them it gave me the ability to critically reflect on myself. If I had only studied business, I might understand financial instruments, but I wouldn’t have developed the same awareness of the world. Our education system needs to be more well-rounded. We need more civic education, more courses on practical life skills—honestly, even lessons on how to love and build community.

Since then, I’ve gone back to Iraq a couple of times, and I traveled to Ukraine after the war started. I got tired of constantly fundraising, so I shifted toward policy work. Now, I help craft legislation—essentially, I’m a lobbyist, but unpaid, so they call me an advocate. That’s where I see democracy in action. I’ve been in the rooms where laws are being written, and I know how much impact everyday people can have.

Recently, I’ve been volunteering with AOC’s team. Everyone has opinions about her, but from the inside, I can tell you—she listens. If you live in New York, I encourage you to get involved. One practical note: to vote in the upcoming mayoral primary, you need to be registered as a Democrat by February 14. No Republican is going to win this race, so if you want to have a say, that’s the deadline.

XJW: To wrap up our conversation, I’d like to ask everyone: As we enter the next four years—a very transitional period—many people are feeling anxious, apprehensive, or uncertain. How do we keep moving forward? What actions and resources can we use to continue pushing for sustainability?

WM: Thank you—I’ll go first. I think we need to stay inspired, and I can’t tell you how to do that because it’s part of everyone’s personal journey. But inspiration is a catalyst. We also need to stay informed. I believe in diversifying the perspectives we engage with—within reason, of course, because some minds simply won’t change.

Beyond that, connecting with community is essential. I host a monthly community discussion series in different Brooklyn neighborhoods, where I pair an artist with an arts administrator to discuss topics related to sustainability and community. It serves as a third space for connection, something I’ve been practicing for about 15 years—holding events and creating space for people to gather around issues that directly affect us.

Tomorrow, for instance, we’ll be at I AM CARIBBEING (1399 Nostrand Ave in Flatbush) for a film-focused event. We’ll screen a short film by Naima Ramos-Chapman, followed by a conversation with Melissa Lyde, founder of Alfreda’s Cinema. It starts at 6 PM—come if you’d like!

But above all, I think it’s crucial to connect with yourself. That’s the most important relationship you can cultivate. My own connection with myself has been the foundation of my work in sustainability and has helped me connect with others in meaningful ways. I try to be spirit-led, which means making choices that feel right in my body. If something doesn’t sit well with me, I don’t do it.

I encourage more of us to tap into that wisdom—our brains aren’t the only organs that should guide our decision-making. We need to start feeling through life. And beyond that, we just need to remember to breathe.

WC: Yeah, I hope to be where you are one day. We’re all on a journey. If I spoke to my 20-year-old self, I’d probably hate me now, but here we are.

What would I suggest? I think deep down, we all know what needs to be done. The challenge isn’t knowledge—it’s action. Honestly, I’m more worried about AI, climate change, and the next pandemic than I am about Trump. We already know the solutions for Trump—it’s just a matter of whether we’re willing to put in the work.

Posting on social media is great, but do we follow up? Do we seek out the truth beyond headlines? I’ve learned that I don’t have all the answers. Sometimes, it feels like social media creates an illusion where people act as if they do. But I’ll be the first to admit—I don’t. And that’s why I need you. We complete each other.

S: I think we’re already doing the work. It reminds me of how, in education, I often complain about the lack of actual education happening. But in that absence, we begin to understand what true education is.

Maybe that’s what applies here too. The work is happening underground, in ways that aren’t always visible. So many people are working, living, and even sacrificing for what we believe in. And all of that adds up. It really does. The things we long for are often the things we don’t have yet. But recognizing that absence helps us understand what we’re striving toward.

SF: I agree with everything that’s been said. We need community resources. Honestly, I think we need a market collapse for real change to happen. And we need money—actual investment—to make that change possible. But we can’t have it all at once.

XJW: Great points. And speaking of resources, during our dinner before this panel, we talked about how we’re not just interlocutors—we’re also listeners.

So now, I’d like to open up the conversation to the audience. If anyone has questions or wants to share how sustainability and environmental issues show up in your own field, we’d love to hear from you. It doesn’t have to be related to the arts or activism—any perspective is welcome.

Q & A

Audience Member 1: I don’t really have a question, but Eliana and I grabbed some food before this, and as soon as we sat down, the first thing she said was, “It’s been a hard week.”

We started talking about how we got to where we are in our careers—she’s in bio-design, and I’m in landscape architecture. We shared our paths, and she told me about how her mom is a doctor. For a long time, she thought she wanted to be a doctor too.

What I’ve taken away from our conversation, and from everything shared here tonight, is that even if you’re not doing exactly what you expected, your work can still be healing. Maybe it’s not healing people in the medical sense, but it’s healing the planet, communities, and systems. It’s about collaboration and creation.

I’ve also been reflecting on something you said earlier—that Trump isn’t new. We’ve been through four years of this before, so we have some idea of what to expect. When he was first elected, I was 17; now I’m 26. In some ways, I’m more pessimistic because I’ve seen so much more of the world. But at the same time, I’m more optimistic because I know we made it through once—we can do it again. It will be difficult, but history keeps moving forward.

I don’t know if that was a question, but that’s what I’ve been thinking about.

WC: I’d add to that. Yes, we’ve seen this before. If you follow European politics, you’ll know what happened in Hungary and Turkey. Each time, there’s a little less fight in us, and authoritarianism gets stronger. The more we normalize this behavior, the harder it will be to undo.

Also, I don’t think we need to romanticize struggle. There’s no reason why certain groups should have to suffer for another four years. Why not two years? Why not just one day? Why aren’t Democrats literally sleeping in Congress until something gets done? We all know the stakes—so where is the leadership?

I’m not a politician, but if they’re not stepping up, then we have to. Whether it’s here, in our communities, or beyond, we need to act. No one should have to suffer more than they already do. The Civil Rights Act didn’t have to wait until the 1960s—it could’ve happened sooner. That’s what makes me angry. If I had been born a different race, gender, or at a different time, my life could have been filled with suffering. I don’t want that for anyone. That’s why there’s urgency.

Audience Member 2: Something I’ve been thinking about is redefining currency. Money is just one form of currency, but it’s not the only one. I wanted to ask all of you: What are some non-monetary currencies that you’ve encountered or found useful? If we’re talking about market collapse, we also have to rethink value.

SF: That’s a great question. Recently, I’ve been thinking about skill-sharing. I taught someone how to electroform jewelry, and in return, they took me paddleboarding. Shared skills and resources are some of the most transformative ways I’ve seen people create and redefine their own economies.

WM: I completely agree. I’d also say seeds are a crucial form of currency—and they will become even more valuable. But we can’t separate currency from the systems they operate within. That’s really what needs to collapse and change.

Money may still exist, but it doesn’t have to function within the framework of hyper-racialized capitalism.

In practice, I interrogate the idea of value—what it means and how it’s assigned. The concept of a "cost of living" has always seemed absurd to me. A big part of my liberation practice is rethinking value, especially in community with my friends. We look at mutual aid models like susu (a community savings system) and engage in skill-sharing. Black femme and natural spaces have long had these structures, rooted in ancestral knowledge. There are blueprints for alternative economies—we just need to engage with them.

S: That reminds me of a research project I worked on at a museum. I came across these raffia textiles that were once a form of currency in parts of Africa, particularly in the northwest. They were beautiful and deeply tied to the land.

That made me think about our historical relationships with plants and fibers—how they’ve been considered valuable at different points in time. These so-called mundane materials, like the grass growing through cracks in the sidewalk, have been essential for centuries. Some of these ancient cellulose fibers have existed for 155 million years, yet today we barely notice them.

At different times in history, what we now dismiss as weeds were considered incredibly valuable. Maybe it’s time to reconsider what we truly assign worth to.

WC: I don’t think I’m entirely qualified to speak about currency, but your question made me reflect on something relevant to many people—those trying to distance themselves from platforms like X or Instagram. Personally, I only use Instagram and haven’t been on Facebook for a long time.

I think a key issue is how power is concentrated in very few hands. When Jenny started IMPULSE, one of the first things I said was, “I don’t need anything from you—what can I do for you?” Because we need to diversify power. That’s part of democracy.

Look at what’s happening with Instagram and Meta. The rich are consolidating power, funneling value through just a few platforms. And now, Whitney can’t even speak freely because of this moral dilemma. So when I think about currency, I think about diversification.

I don’t make objects anymore—I am my own brand. That means I’m very intentional about being on multiple platforms, both traditional and unconventional. I engage with people in Congress, in the statehouse—I don’t want to rely on any one system.

Big shoutout to Hyperallergic—I won’t embarrass anyone in particular, but they truly understand the importance of diversification.

Right now, I think one of the biggest challenges we face is the cost of education and healthcare. If we could break these issues down and clarify them for people, that would be incredibly impactful. Healthcare costs, for example, are tied to insurance companies and Congress, but we’re all suffering from it. Social media operates in a similar way—power is concentrated in just a few hands. That’s how I think about currency.

Audience Member 3: Hi, my name is Lynn. I’m a young queer artist navigating life in the city, and all my friends are young queer artists as well. Lately, I’ve been having the same conversation over and over—people are scared.

As an artist without an established practice, I feel this overwhelming pressure to do something. Do you have any advice for young artists looking to incorporate environmentalism into their work? And how do you find inspiration and hope in your everyday life?

WM: I want to reiterate something Will mentioned—diversifying your medium is your responsibility.

You’re an artist, no matter the space you occupy. Use your practice to enhance that space, whether it’s politics, a phone bank, a corporate setting—wherever you are. Apply your creative process to any medium you choose.

If you don’t have a defined medium yet, start by identifying your values and ethics. Build from there. Right now, as artists, the world is your canvas, and everything needs improvement. Art enhances the world—it creates beauty, freedom, and new ways of thinking. And we need that now more than ever.

XJW: And Embodied Earth partners with an amazing organization called Artists Commit.

NJ: Yes! Artist Commit is a fantastic organization that Embodied Earth has worked with. They provide resources to help artists integrate sustainability into their work without drastically changing their existing practice. They encourage artists to be mindful of their process and make small, meaningful changes. Definitely check them out.

WM: There are also some great tangible resources—Artist Commit, Key Futures, Julie’s Bicycle, the Gallery Climate Coalition. If you want specifics—like which paints or materials are more sustainable—let me know. But ultimately, the most important thing is to apply these ideas across mediums.

NJ: I’d also add Biofabricate to the list. They host conferences in New York and Europe showcasing groundbreaking sustainable materials—like clothing made from rocks or concrete that grows. There’s also Newlab in Brooklyn, which features cutting-edge technology, and they’re often open to the public. We have an amazing community in New York.

SF: I want to add to the previous question—yes, do as much as you can to make an impact, but the pressure can be paralyzing. It’s crucial to have fun, spend time with friends, and create community. That’s just as important as the work itself.

Audience Member 4: Great panel so far—thank you all for your time. When we talk about art and climate, one topic that comes up often is activists defacing or destroying artwork in protest. I’d love to hear your thoughts on that. How do you integrate your values into your response to those actions?

WM: Rather than focusing on the act of defacing art, I think it’s more important to address the broader issue—the waste and inequality perpetuated by the art industrial complex. Museums and institutions hold power, and that power should be used for discourse and education.

Some museums have actually invited activists into their operations to collaborate, which is what I want to see more of. Institutions should be listening to activists, giving them a platform, and finding ways to coexist.

At the heart of this, we need to ask: Whose art are we preserving? And if we don’t have a livable world, what is cultural preservation even for? This is an urgent conversation, and we need to nurture this intersection between art and activism.

NJ: We have time for one or two more questions.

Audience Member 5: I want to weave together some of the ideas we’ve been discussing, particularly around alternative currencies.

My name is Benjamin Von Wong. I’m an artist—despite my Asian face, I’m 38 years old and have been creating climate-focused art for almost a decade.

When we talk about alternative forms of currency, we need to recognize how figures like Trump wield attention as a currency. He’s mastered the ability to hijack our focus, draining our energy and making us feel powerless. Every time we engage with the news cycle, we’re choosing to give away our attention.

As artists, we need to counterbalance that. Instead of just adding to the infinite scroll of content, we should provide context. What does it mean to be alive in this world? How can we create work that fosters real connection and meaning?

In climate disasters—like those happening in LA—it’s not wealth that determines survival, but community. Who will show up for you? What skills can you contribute? Can you build, mend, grow food? If you’re unsure of your role, start by learning. Follow your curiosity, build skills, and surround yourself with people who care about the same things you do.

Too often, we focus solely on the urgency of the climate crisis. But if you’re only trying to save the world without learning how to sustain yourself, you’ll burn out. The key is to find joy in the work—to wake up excited about what you’re building with your friends. That’s how resilience is created.

We’re here today not just to learn, but to spark connections—to realize that we’re not alone in this. There are infinite ways to contribute.

NJ: You can find everyone’s platforms in the program—just scan the QR code.

Audience Member 6: Hi, my name is Urja, and I'm a curator. My comment is more of a series of questions. In exhibition-making, sustainability is often discussed in terms of content, but not in the materials or format of exhibitions themselves—the white cube space, for example.

Elements like latex paint, climate control, track lighting, shipping, and transportation all contribute to a high carbon footprint. How can we rethink exhibition design to align with climate-conscious practices? The white cube is a modernist construct, and we should consider ways to move beyond it without making exhibitions at the expense of planetary resources.

I'm exploring alternatives, such as printing on cloth and eliminating latex. But negotiating these changes with institutions is a challenge—they often resist these shifts. This is something I’ve been grappling with.

WM: There’s a lot of work being done on sustainability in exhibition-making. One great resource is the Healthy Materials Lab at Parsons, which has an exhibition materials spreadsheet listing alternative materials. The Gallery Climate Coalition also offers valuable resources.

The Design Museum in London has a curator-focused decision tree that helps rethink exhibition-making within a sustainability framework.

As for disrupting the white cube, there’s so much to unpack. In terms of logistics, we're researching shipping emissions—comparing sea freight, air transport, and rail. If you’re interested in contributing to that research, let me know.

The Guggenheim has extensive resources on its website covering some of these concerns, available in Spanish, English, and Basque. Those are good starting points.

SF: Yes, the Healthy Materials Lab at Parsons is a fantastic resource. My work is on a much smaller scale than major institutions, but even at this level, packaging alone involves so much labor and petroleum-based materials—so much foam.

There are potential alternatives, like mycelium-based packaging, but right now, these solutions aren’t widely implemented. The responsibility shouldn’t fall solely on artists—it should be on galleries and institutions to implement sustainable practices.

For my own projects, I’ve tried to cut costs by sourcing free crates. I put out a call on Instagram, and a company that was moving storage donated a huge supply. The foam inside was incredibly high-quality—something that would have cost me thousands of dollars.

Shipping costs are astronomical. For a recent show in Los Angeles, the cost of packaging, crating, and shipping was $40,000. That’s considered normal in the art world, but it’s unsustainable. I’ve learned a lot just by reaching out and pooling resources, and unfortunately, Instagram has been a useful tool for that.

Audience Member 7: Hi, everyone. Thank you for this incredible panel. My name is Aliana—I’m a coastal restoration researcher and a huge advocate for the intersection of art and climate.

I see art as a way to imagine possible futures and redefine our relationship with the environment. But there’s often a gap between artistic expression and tangible impact. How do we bridge that divide? How do these exhibitions translate into real-world action?

How does your work create new pathways for change, and how can we ensure that these ideas lead to direct, meaningful impact and how do we put them into action?

S: I love that question and it's something that I'm thinking about all the time. I’m often asked whether I'd be interested in having a company and developing my material and using it for different kinds of objects and products. But I'm an artist, and I don't know if that's the core of my mission. I'd love for somebody to work on that, so if you want to come and do it you should!

But I think of it in two ways. One is that there's different kinds of scales that we work at, and it's often a lot of the labor that happens in isolation and in small placements, at smaller scales, that provide opportunities for envisioning something new, which eventually makes its way into the mainstream. And I think that's very much already been the case with bioplastics, biomaterials, organizations like Genspace. I was watching one of their videos, and they're talking about, if you can imagine a world where biotechnology is in your hands the way a personal computer is in your hands, it's a direct parallel in that if we had access to community labs where we could understand what was in our food, what’s in what we eat—all that to say that I do think that these things are scaling and will continue to scale.

And the second one for my work specifically, I don't know if global, large-scale solutions are what is needed right now. I'd be really interested this sort of symbolic and poetic meaning of at a specific kind of manageable scale, where we’re using the materials from our land, the ones that are invasive, the ones that are sort of our leftovers, the ones that are becoming compost, and we're creating meaning by adding something of ourselves, our bodies, our time together, into those materials.

I think that that is fundamentally the power of artistic practice and artistic labor, especially when it is shared. When artistic labor is at that neighborhood-community scale, that’s when I get really excited.

WC: I think this could be a six-hour reply that I will truncate as fast as I can. But I think about this a lot. I've been out of grad school for like 10 years, and I think I went through this thing where first I wanted to do the hustle—I wanted to be in Pace and MoMA—and then I realized it's just not what my life is about.

So what I found was that the white cube—you're talking about a commercial gallery, let's say— their purpose is to sell things. It's a show. You could put a card in there instead of a pen name, and it does exactly the same thing. So they're not incentivized to create a good show, they're incentivized to pay the rent.

Museums are kind of like Art 101. But the problem with most museums is that when they’re funded through trustees, or people who are rich, or people who have an extra 5 million to invest, they tend to not care about the same things that we care about. That doesn't mean that they're bad people.

So I mean, when we talk about MoMA, let's say and I put it out there—if you hear me, MoMA, I’m talking to you, but I also want to show—the thing we grapple with for MoMA is that most of their trustees are rich people who are very conservative and have a track record of supporting Republicans, or are Republicans. But at the same time, they’ll throw up a show about diversity, equality, and their logo will have, like, the rainbow. But at the same time, some of the trustees are the biggest donors to Republican causes.

I love museums as a concept, and I think it works, but at the end of the day, the trustees are the decision makers, and they’re the ones who get to choose and okay who the directors of the museum’s everyday operations are. So all the directors, at the end of the day, whether they agree with the trustees or not, have to make the trustees happy. Always follow the money and the intent.

But individually, I think what we're doing exactly that right now, like when I transitioned from a commercial gallery artist. When a pandemic started, I rented a window gallery in lower Manhattan, and it was a not-for-profit. I’m a disabled veteran, so I get a certain amount of money, and I use that money for the gallery because I feel like it's kind of blood money. I don't want to be comfortable. If someone in Iraq isn’t comfortable, then I'm not comfortable. These are the ghosts in my head. I'm stable—I live good, I eat good. Anything excess I give back to the community. I don't want to give it back to the government, because they would just buy another bomb or plane. So I use the excess money to rent a window gallery. And there's no profit motive—I don't charge anyone anything. So that's one way.

You have artists who feel like they’re stuck in a capitalist funnel. You need to take how the weight manifests and put it out of the way. There's nothing wrong with having a show at MoMA, but that, to me, is only a small slice of who I am. That's like 1% of my life’s resume. This is part of my practice, too—I'm standing up, I talk a lot, and maybe after today, 20 people will know a little bit more about me, and maybe want to pick up my baton and take it from there. Just don't get stuck on any platform. If you have something that needs to be said, I'd love it for you to say it. Do it in these Q&A’s, or on Instagram. I think that's one way to break out of that—thinking about, “can it affect people?” Just bring it to the public.

SF: I don’t know if people are familiar with BioBAT Art Space in Brooklyn. It’s a great space for artists and it’s also a nonprofit.

NJ: I think we’re out of time, unfortunately.

XJW: Thank you so much everyone for lending us their ears. Thank you to all four of our panelists. Thank you Patagonia Brooklyn, and also shout out to their work in activism. They have some amazing resources on their website, and they are really committed to preserving Arctic wildlife as well as climate change. Nicole, do you have anything to add?

NJ: Yeah! Thank you so much everyone for coming. We're really grateful that you all chose to spend your evening here with us. We know that time is precious, and we're very, very grateful to spend time and community with you. Please stay in touch with us—we have a sign up sheet in the back. You can add your email if you'd like to hear from Embodied Earth or IMPULSE. We will be publishing a transcription of this panel to IMPULSE, so you'll be able to return to the words that were spoken tonight again and again, which we're very excited about. And finally, if you'd like to stay in touch with us or our panelists, you can also check out the event program that's on the QR code on these posters. Thank you all very, very much, and have a good night.

The Art Lover’s Guide to the Environment: Art and Climate in Dialogue panel was held at Patagonia Brooklyn on January 30, 2025.