Acky Bright’s Graphic Impulse

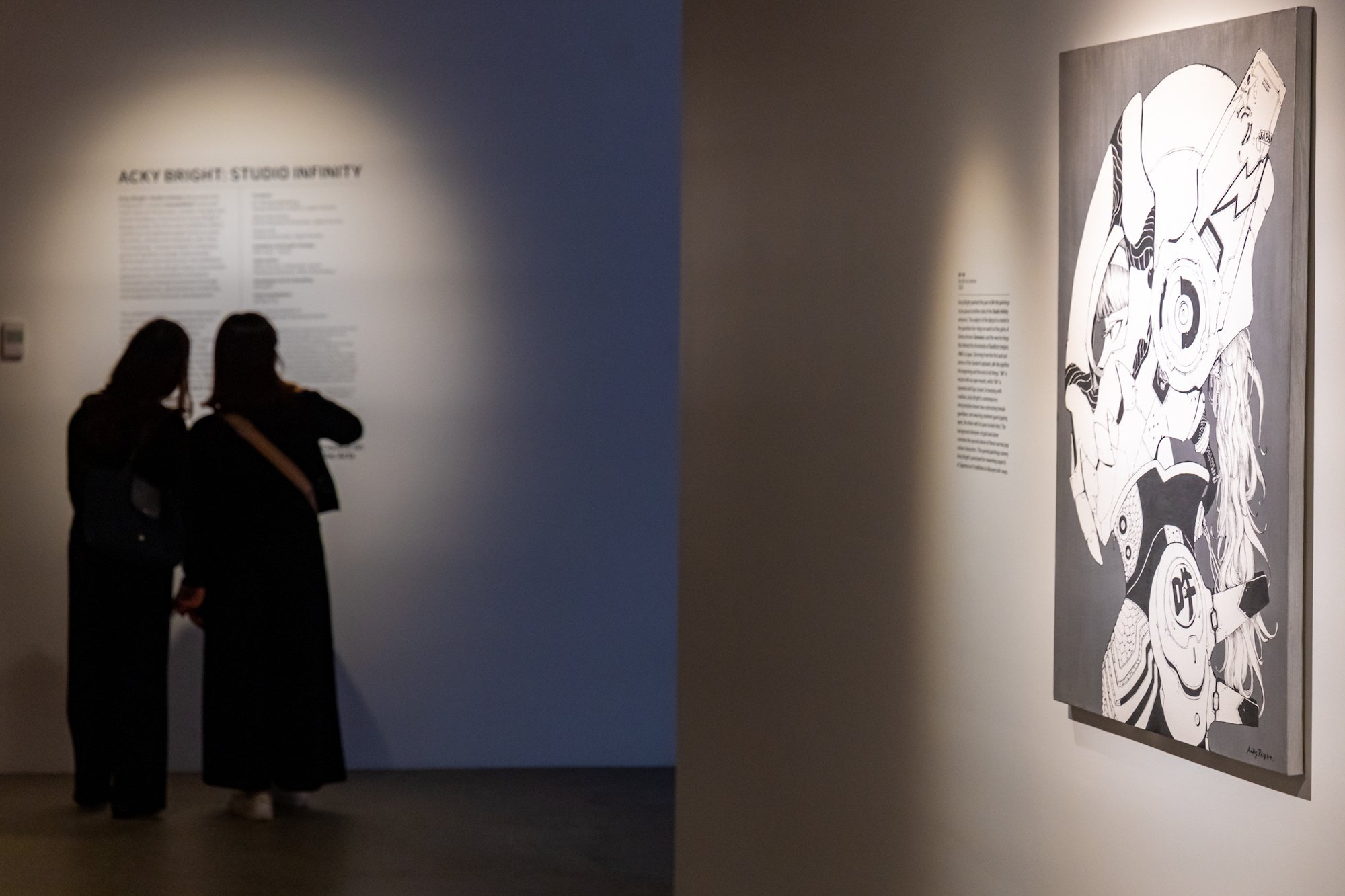

Upon entering Acky Bright: Studio Infinity on view at Japan Society, visitors must choose between two paths demarcated by a large, long wall: Follow to the right along the front of the wall, where a rectangle of warm light emanating from a glass cutout in its center guides the way, or venture straight ahead, where blue light and exuberant heavy metal pop music spill out from behind the wall's left edge.

Ultimately, these dual paths connect, forming one route that wraps around the titular attraction of the exhibition—what might be described as a gallery within a gallery, a viewing room meets stage meets art studio. The center wall has been cut out to fit a custom window measuring roughly 8 x 12’, outfitted with three panes of transparent glass. Inside, the walls connect to an elevated wooden platform about four inches off the grey cement floor. When the exhibition opened in late September, the walls, floor, and glass shined pristinely, ripe with fresh paint and polished surfaces. Over the course of the show’s run, Acky Bright has obliterated the boundaries between these surfaces and transgressed museum and general societal mores by drawing directly all over the walls, glass, and even the floor with a thick, black marker, resulting in a large-scale, vibrant mural.

Rendered by the artist during many live drawing performances scheduled throughout the exhibition, a plethora of characters and imagery populate the teeming, sprawling, and densely packed work—snakes, dragons, mutant bunnies, a grinning young woman posed with a skull, a tiger, fish, a troll with horns, a fossilized yet animated dinosaur, a mutant goat skull, a bald and bearded man whose eyes appear hollow, frogs, feathers, flowers, and flames.

In an interview with IMPULSE Magazine translated through his manager, Bright elaborated on his live drawing practice: “I categorize my live drawing as a performance ... I'm taking the artmaking process because it is an essential part of what I want the audience to feel. I want them to know that there is a process behind each small part of my work. The activity behind the art is very important.”

Bright does not make preliminary sketches. Instead, he improvises the entire performance. In our conversation, he explained the rationale behind this approach: “If I make a mistake—I make mistakes all the time—it’s a different form of thinking to include these mistakes. By including the true, unfiltered process, I want the audience to have fun by watching my artworks, and I myself to enjoy.” It’s a practice that emphasizes the reflexive and responsive relationship between the audience and himself. For example, if a child is watching, the artist will more than likely draw cute characters that would be identifiable to kids. With an older audience, he may venture into, say, a fierce and hellish metal mutant dragon, accommodating an intense range of forms and aesthetics in an operatic graphic tour de force. “To me, art shouldn't be some medium only for wealthy people. It has to be for a mass audience, for the public.” He continues, “That’s why I'm holding one marker doodling. That's something that kids do, you know. That’s supposed to be the art.”

Like the protagonist in his favorite American graphic novel Batman, the artist created his professional name “Acky Bright” as a pseudonym to mediate the dual lives that he found himself living at the beginning of his professional studio art practice, roughly five years ago. As his art became increasingly popular, he created the persona out of the necessity to keep his identity as an artist a secret—not from villainous foes but from employees who worked at the design firm he owned. As the artist’s work gained popularity, he had to “face the moment” and came up with the name Acky Bright, which, ironically, incorporated his real-life identity—Acky derives from his Japanese surname while Bright is part of the name of the design firm that the artist owns in Tokyo.

Bright’s big break came in 2020 when a former DC Comics Batman chief editor discovered his work and hired him for his first project with the graphic novel franchise. Although Bright notes that he regrets not having time to workshop his professional name more as it was born out of urgency, he acknowledges its benefits. Alphabetically, it puts him at the top of the list in many of the popular culture conventions where he performs his live drawings. More nuanced, the artist commented on the freedom that the ambiguity of the name provides—it can’t be easily pinpointed to any particular background or identity, a strategy similarly employed by Batman to shed his identity as heir-turned-mogul Bruce Wayne. Furthermore, just as Bruce Wayne’s connections and day job sometimes benefit his dark, rogue alter ego’s pursuit of justice, Bright’s experience running a design firm has aided his ability to execute ambitious artistic collaborations with global brands such as BMW, Meta, Hasbro, Netflix, and McDonald’s.

In his work with McDonald’s, Bright pulled from the commonly used representation of McDonald’s in Japanese anime and Manga as WacDonald’s and WcDonald’s (popular due to copyright protections) tracing as far back as 1981. He builds an alternative McDonald’s universe surrounding its core characters, a crew of WcDonald employees featured on physical ephemera such as cups, fry and sandwich boxes, and most elaborately on the to-go paper bag. In developing the characters, he focuses on two core elements: personality and likeability. “The goal of the ad is to pull people in based on imagery and the message,” he pointed out. Emphasizing muscle and bone structures across his work, he also pays close attention to creating the crew in a way that would be recognized in any country. On the overlap between advertising and art, he says, “Some people say that advertisement is not art, but I don't think so. There is no boundary for anything anymore.”

Indeed, while the artist was the first artist to collaborate with McDonald’s, artists who pulled from popular imagery and everyday consumer products defined the entire pop genre. Andy Warhol himself worked in advertising prior to becoming Warhol. Then, there is the contemporary example of the collaboration between Louis Vuitton and Takashi Murakami, who heavily incorporates anime in his work. In Murakami’s 2000 Super Flat Manifesto, he linked a tendency towards two-dimensional imageries to consumerist sensibilities within local and global contexts. The paper bag itself appears often in modern and contemporary art, from David Hammons’s Bag Lady in Flight to G. Peter Jemison’s paper bag works from the early 1980s. The flat-bottomed paper bag, itself, designed by Margaret E. White and Charles B. Stilwell in the late 1800s, is in the Museum of Modern Art’s collection and currently on display.

That said, Bright does not cite any art historical references; instead, he credits Disney and Pixar as influential to his development, stating, “One of the big inspirations was the Disney animation film Beauty and the Beast…The lamp character—I thought, oh my god, you can make anything, transform any kind of item.” The artist’s affinity for such disparate characters as Lumiere and Batman seems fitting, considering the balance of cute and cool meets goth metal punk in his imagery. In the exhibition, an entire section of the wall showcases the artist’s process of developing the WcDonald’s universe and its crew: Sweet, Charm, Flurry, Whisp, Steel, Meister, WcDizer 3000, N, Burg, and Moon. Out of this unique, imaginative group, the artist shared, laughing, that the most popular was the most traditional: Burg, an adaptation of the nostalgic classic Hamburglar character. Responding to a question regarding formal historical or contemporary art influences, he stated: “I don’t go to any specific type of artist because I'm doing so many things. I think my activity itself can be art, not just the result.”

Ah-Un, an acrylic diptych, flanks the glass window in the center of the front-facing wall that bookends the show. It features two profiles of a young woman clad in armor, wearing a large helmet resembling the skeleton head of a mutant animal, with large teeth bared at the opening of the top and bottom pieces. In the left panel of the work, she faces the left with the helmet closed over her face against a silver background, and in the right panel, she faces the right with the helmet now open, against a copper-gold background. Titled after the sounds of the first and last letters in the Sanskrit alphabet, Ah-Un refers to the lion-dog statues placed in Shinto shrines in Japan and the warrior kings that guard them. Traditionally symbolizing beginnings and endings—as reflected in the inhalation and exhalation of breath and the shapes the mouth forms when producing these sounds—the left statue’s mouth is closed, while the right statue’s mouth is open in these spiritual statue pairs. Additionally, ah-un is commonly used today in everyday conversation to communicate agreement. The combination of historical references, contemporary female manga-style figuration, and the everyday usage of the phrase is emblematic of Bright’s approach to visual culture. He expanded on his work's broad and eclectic mixture of inspiration and influence: “I am collecting different items. Instead of trying to express something different, I’m digesting it.”

Acky Bright: Studio Infinity is on view at the Japan Society through January 19, 2025.

The artist will complete his mural drawings during the below dates and times:

January 16 & 17, 11am to 7pm;

January 18, 12pm to 7pm (artist talk at 4pm);

January 19, 12pm to 7pm (final day of exhibition).

Edited by Xuezhu Jenny Wang