In Conversation with Muhammad Toukhy

In an era dominated by screens and an overwhelming abundance of data, our digital lives are reflected back to us with uncanny precision. This phenomenon prompts a critical inquiry: How do we meaningfully engage with art in virtual spaces, and what does audience participation signify when the gallery exists online?

The Pond of Person A (2025), an online exhibition launched on April 18, 2025 through the New Media Caucus’s Header/Footer Gallery platform, emerges as a collaborative endeavor between digital art researcher Bowie Bo Gyung Kim and multimedia artist Muhammad Toukhy. The project responds to the aforementioned questions through an interactive format. Set within a web-based virtual environment, this project invites audiences to wander a digitally rendered island, reimagining the role of the spectator as both navigator and participant in a mediated landscape.

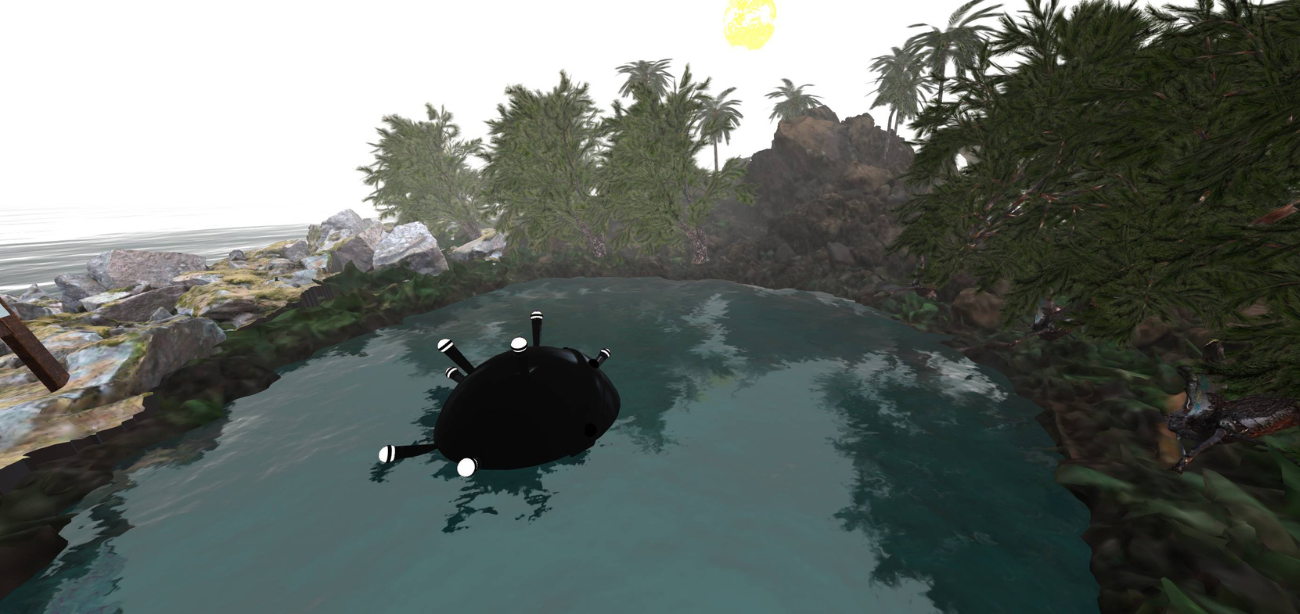

The Pond of Person A centers on Toukhy’s interactive web-based artwork KISMET (2024), which integrates audience input into the artwork. There, the “Mic-Bomb” designed by Toukhy serves as a trigger for interaction. Upon activation, KISMET listens through the audience’s microphone, transforming any input—spoken word, whispered phrase, or ambient noise—into dynamic visual responses within the digital environment. Pillars of light rise and fall in rhythm with the audience’s voice, rendering the audience not merely as observers but as co-creators. In this mediated exchange, the audience experiences what it means to be both engaged by and embodied within the artwork itself.

In the conversation between Kim and Toukhy, the curator and the artist unpack their online exhibition and reflect on the nuances of audience participation, self-awareness, and the evolving nature of artistic presence in virtual spaces.

Bowie Kim: Can you tell me about KISMET?

Muhammad Toukhy: KISMET is an interactive experience that explores the idea of constant input—the notion that the world is never silent and that waves of information, sound, and presence are always moving through space, even when unnoticed. It reflects on the invisible yet persistent currents of communication that shape our environments, whether through physical vibrations, digital signals, or human voices. In KISMET, the act of listening becomes a way of witnessing. The space itself responds to even the faintest input, which is a reminder of how nothing is actually static. The work invites the user into a relationship where presence alone leaves an imprint.

KISMET was developed as part of a larger project I created in 2024 in collaboration with artist Sharon Rose Benson. Sharon and I initially began our collaboration by making a film together—she wrote it, and I shot and edited it. The film was later shown as part of the group exhibition at the Crypt Gallery in London. During the development of the broader project, I started working on this interactive platform using a game engine. I wanted to create a piece that would echo the voices inhabiting the gallery space itself. After the show ended, I was left with this software work and began exploring what kind of life it could have outside the context of the original KISMET project.

I was curious about its potential as part of a virtual exhibition. At the same time, I felt hesitant because for me, the piece was deeply tied to the physical experience of space. One major shift in this new edition was that it no longer simply existed as a digital file running on a local computer or as a copy that could be downloaded. Instead, it became anchored to a specific online location: the KISMET_LIVE domain. In hindsight, this shift elevated the work. It brought back a sense of physicality. It wasn’t just an .exe file projected in a gallery anymore; it was the gallery space itself.

BK: I noticed key differences between physical and virtual exhibition spaces while I was curating the virtual art project. Virtual exhibitions require active audience engagement; the experience can be entirely lost without the willingness to participate. I’d love to hear your thoughts as an artist who has experienced both.

MT: I’m aware of the risks involved in online exhibitions. People who aren’t particularly tech-savvy might not even try to engage. The question of inclusivity and accessibility is important here. Then again, it’s not as if the white cube has ever been truly accessible either.

But more to the point, I think virtual spaces create a very particular way of “consuming” art. No one sees you, at least in theory. In a physical gallery, there is always a certain level of self-awareness. You follow social codes and cues, perform interest, and behave as though you’re engaged. A lot of acting is involved.

In the virtual space, it’s more like the Ring of Gyges. When no one sees you, you can do whatever you want. That anonymity holds the potential for a more raw and unfiltered encounter with the work.

Still, I think KISMET complicates that. As a user or viewer engages with it, they receive feedback. There is a feeling that the work is, in some way, listening, because it is. That presence shifts the experience again.

BK: KISMET is fascinating in how it absorbs unnoticed surroundings while its light pillars visually encourage the audience’s active participation. Thus, it invites both active and passive participation. What do you think about the synchronization between sound and the light visual effect in KISMET? What kind of effect do you think this synchronization creates for the audience?

MT: For me, it brings up ideas of physical experience and realism by syncing the two together. It is a way to reconnect what is happening on the screen with what is happening in reality. The synchronization serves as a reminder that the digital space and the real world are connected. Even small sounds have a visible effect.

BK: How can we compare hearing sound through the auditory sense versus seeing sound as a visualized form?

MT: I often think about how senses overlap, especially when it comes to sound. In KISMET, sound becomes something visible. The glowing pillars rise and fall in response to live microphone input. Hearing and seeing are both ways of receiving, shaped by the body and the environment. I do not think of them as separate. Our brains constantly weave different senses into a single experience, even though our bodies treat them as distinct channels, because that’s how are bodies were made to survive.

Imagine if touch, taste, and sight were processed by the same neurons without distinction. You wouldn’t know if something you felt was actually something you saw or something you tasted. That would be crazy. In KISMET, I wanted to explore how sound could shape space and presence. I was thinking about how something ephemeral, like a voice or a noise, could leave a mark in the environment.

BK: On the virtual island in The Pond of Person A, the audience navigates alone—they face no one but themselves, reflected in your artwork. Yet, their movements are still shaped by their sense of belonging. This makes me curious about how society functions within virtual space. Do you think a virtual space can form or constitute a society?

MT: Absolutely, I think virtual space can form a kind of society. It just works differently. Instead of laws and borders, it’s built through presence, shared symbols, avatars, and, of course, interaction.

Hakim Bey talks about this in Temporary Autonomous Zone. He says the TAZ is like a temporary uprising that creates a space of freedom, then dissolves and appears elsewhere. That’s how a lot of online communities work. Take early Minecraft servers: people built towns, made rules, took on roles, and even formed economies. It was temporary, but while it lasted, it was real. People remembered it, talked about it, carried parts of it into the next space.

BK: Then, how do you view the experience of a user acting alone in a virtual environment?

MT: The space itself is shaped by collective design, shared references, and expectations. So even if you’re not talking to another user, you’re still responding to something others have built, imagined, or left behind. That’s a form of dialogue. You’re in conversation, just not necessarily in real time.

BK: Which aspect of the relationship between the individual and society do you aim to convey more clearly through KISMET?

MT: Once a space is online, it already becomes shared. It is a place where people from different places can come together, even if they never meet directly. But what is interesting for me is that KISMET might also feel a bit like a confession booth. You can interact with the program, you can say something or make a sound, and no one else will know. Only the system knows. That privacy creates something very personal.

That is also why I chose to place it inside a watery environment. Water feels like an abyss. It is a place where you can throw something, like a message in a bottle, and it might sink and disappear, or it might float and reach someone else. You never fully control it.

I think this reflects something important about society, too. What connects me to another person is not necessarily what we say to each other. It is the fact that we both carry things we cannot fully share. Just knowing that we each have our own hidden parts creates a bond between us. KISMET tries to make that quiet connection feel real.

This interview has been edited for clarity and length.

Bowie Bo Gyung Kim and Muhammad Toukhy: The Pond of Person A is on view at New Media Caucus’s website.