Being an “Art Monster”

What does it mean to be a monster? Lauren Elkin asks this in her latest nonfiction book, Art Monsters: Unruly Bodies in Feminist Art (2023), taking for its title a reference to Jenny Offill’s 2014 novel Dept. of Speculation. “My plan was to never get married,” Offill’s narrator says. “I was going to be an art monster instead. Women almost never become art monsters because art monsters only concern themselves with art, never mundane things. Nabokov didn’t even fold his own umbrella. Vera licked his stamps for him.” As is evident in this quote, the archetype of the “art monster” is someone we instinctively know as male. His divine artistic brilliance allows him to be a monster in his personal life, whatever that may mean. Also evident is how he is made possible by the silent labor of an attached woman, articulating the impossibility of a woman taking up a similar space.

But is it desirable to be an art monster? Should those of us in the business of making subsume or reject our mundane, quotidian, and personal for the sake and in service of our work? In Claire Dederer’s recent Monsters: A Fan’s Dilemma (2023), the term “monster” is nuanced but distinctly bad, and she seeks to reconcile powerful work stained by the monstrous acts of their makers, mostly men but she also mentions the antisemitism of Virginia Woolf. For Elkin, the label of “monster” is firmly feminist, a refusal to adhere to what a woman should or should not be will inevitably earn oneself the title. She recounts Woolf’s famous reckoning, how the novelist deemed it imperative to kill the “angel in the house” in order to write; fulfilling the domestic duties of womanhood was diametrically opposed to any artistic endeavor. Though this was Woolf’s answer, the many artists of Art Monsters offer alternatives, eschewing the choice of woman or artist altogether.

In lieu of replacing one ruling narrative with another, Elkin explains and complicates this dichotomy, weaving loose threads and further tangling knotty questions. The book reads as a collection of scattered inquiries into the links or disconnects between artists, writers, art historians, and feminist scholars. Stitching together these disparate entries is the forward slash punctuation mark: “/”. As Elkin introduces, “the mark itself is the hieroglyphic equivalent of the verb to cleave, which simultaneously means one thing and its opposite. It slashes/tears, but it also strokes/heals.” By presenting a collection of text fragments, some single sentences, others whole chapters, Elkin denies the responsibility of proposing one alternate path. Instead, she offers thoughts and reflections only, no totalizing prescriptions.

A discussion of artist Carolee Schneemann’s Interior Scroll (1975) sets the tone for the book, and acts as a touchstone throughout. In her original performance, a naked Schneemann addresses the audience from atop a table, pulls a paper scroll out of her vagina and begins to read aloud. The scroll resembles an umbilical cord, acting as a proxy for reproductive and artistic procreation, while the artist appears fresh out of the womb herself, smeared in dark gunky paint. The text she reads references dismissive comments the artist received from a critic, expressing discomfort with her work’s “personal clutter,” “hand-touch sensibility,” and “diaristic indulgence.” These phrases reemerge as leitmotifs throughout the book, becoming a shorthand for the feminist strategies employed to counter certain art-making standards, rejecting the universal, sanitized, and impersonal patriarchal work. Further, Elkin adds personal recollections to her academic analysis, remarking on how she felt standing in front of an Eva Hesse sculpture, how her body changed when she was pregnant, and how repulsed she was by Kathy Acker’s writing when she first encountered it. She includes her thought processes, taking the reader along with her to not necessarily any particular destination, and in this way, traces Schneemann’s attention to the personal, bodily, and diaristic.

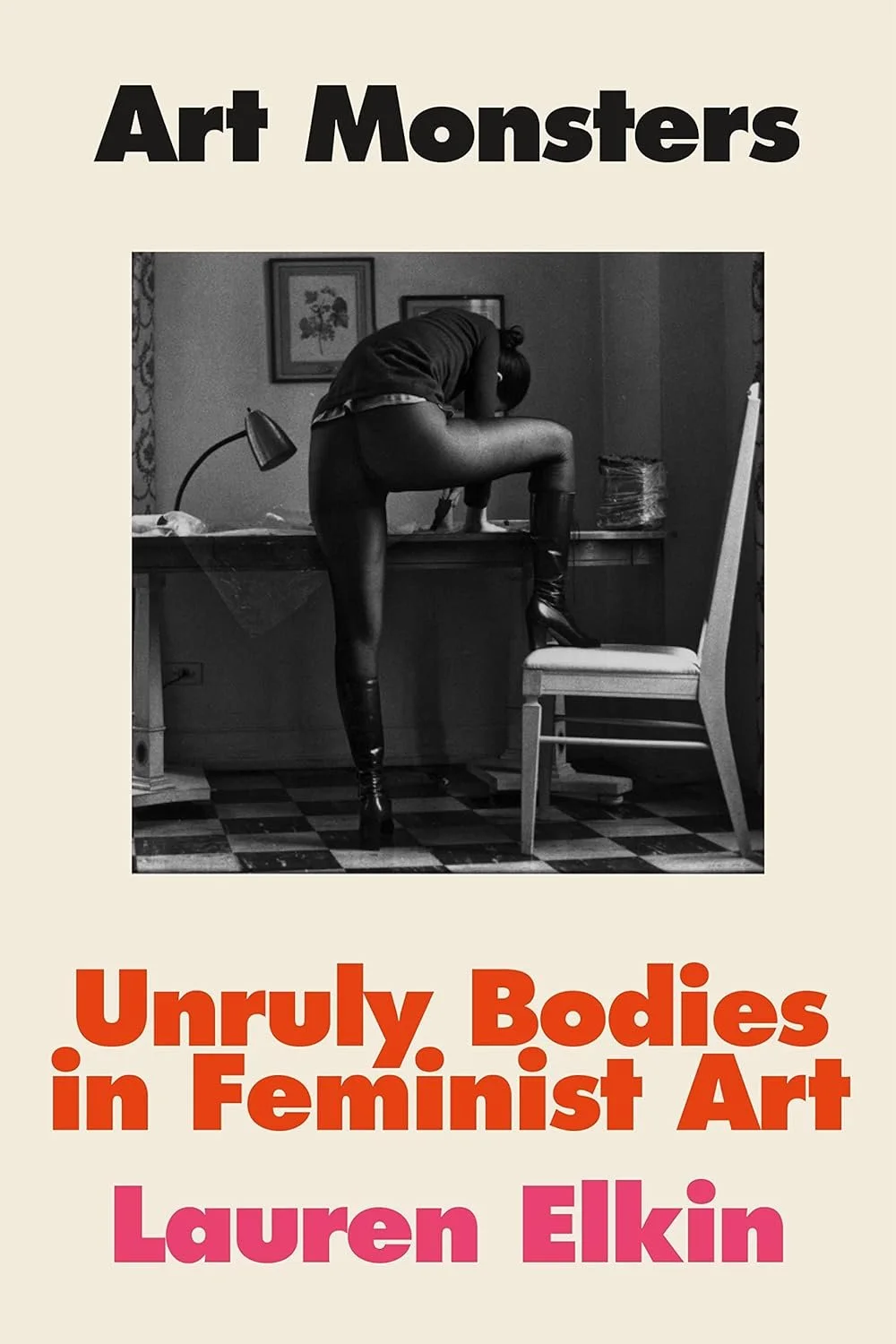

A photo of American artist Hannah Wilke adorns the cover of the American edition. The artist is pictured from the back, bent over a table with a foot propped up on a chair, furtively obscuring what she’s up to. She turns away from the camera, hiding her face behind her limbs. We see neither her work nor her skin, though she is wearing skin-tight leggings with tall heeled boots. She is both artist and subject, person and image. The photo was used as an advertisement for an exhibition at Ronald Feldman Fine Arts Inc., and shows her hard at work making what we can assume are her folded yonic sculptures, most of which are painted ceramics. Wilke enlisted sculptor Claes Oldenburg, her longtime partner in the 1960s and ’70s, to take the photo for her. She steps into the role of artist, turning her back to her partner and the viewer, contorting her body in service of her work. Perhaps this is a snapshot of an art monster in action, a woman refusing.

The cover of the United Kingdom edition pictures a painting by Irish artist Genieve Figgis, an artist Elkin describes as possessing “a wobbly blobbiness that is all her own.” Entirely opposite from the austere, formal, and black-and-white photograph of Wilke, Figgis’s Blue Eyeliner (2020) shows a blurred but distinctly feminine face. She is either applying or removing makeup. Either way, her eye appears as a blue hole in her head, the center of a blooming blue blot. Her face melts into her makeup, which in turn blurs into her raised hand. Here is another art monster, a woman aware of the constructed nature of her identity, a woman who creates and destroys herself. “Art monstrosity, as with Figgis’s painting,” Elkin writes, “stages the dismantling of artifice to reveal that there is no unvarnished truth beneath; the skin comes away with the make-up; hand and face become one. There is beauty here but it is the ucky beauty of entropy, of unmaking, of the smear, the scratch, the slash.”

You Might Also Like: